No proscenium REVIEW:

american dreams are just out of reach in stunning 'port of entry'

Nestled between the Chicago River and Edens Expressway on the northside of Chicago sits Albany Park. This neighborhood is reported to be one of the most diverse areas in the United States, housing foreign born residents from Latin America, South Asia, and the Middle East. On the neighborhood’s southern border sits Fernstrom Fireproof Storage, built in 1929 and spanning 12,000 square feet across three stories. But instead of storing family heirlooms and furniture for safe keeping, the building now houses a living artistic embodiment of its residents’ lives.

Port of Entry is an interactive dark ride experience that takes place in this gutted and renovated storage building; its interior reconstructed to emulate a courtyard apartment building. Developed by the locally based Albany Park Theatre Project (APTP) and Third Rail Projects (TRP), it sees an audience of 28 enter the apartment building where performers, acting as both past and present tenants, guide randomly predetermined groups through their apartments and lives. Throughout the experience, the audience engages with the tenants through lively group activities, silently witnessing events, or one-on-one interactions.

The first stunning element is Port of Entry’s production design. While the courtyard is mostly a suggested space, a majority of hallways and apartments are fully functional and furnished. These spaces are instantly believable, but it wasn’t the quality or quantity of details at work that fooled me. It was the choice of which details were featured that pulled me in–the unconventionally shaped pantries, the sound of planes overhead approaching O’Hare, the fireplace sandwiched between built-in shelving units of equal height. Only when moving between floors, as the stairwell is a neutral, stylized space, did I remember this “building” was a massive set.

Yet, the building’s believability was only part of what made the production design fantastic. It was when the realism faded away, slowly replaced by intense elements of theatrically that left me breathless. Throughout Port of Entry, as tenants convey stories of mundane or intense struggles, the natural lighting and cityscape sounds fade away, replaced with anything from projection mapping to single spotlights illuminating the space underscored by sweeping orchestrations or a cacophony of discordant sounds. These dramatically emphasized moments drew me into each tenant’s story, their joy and sorrow intensely personified.

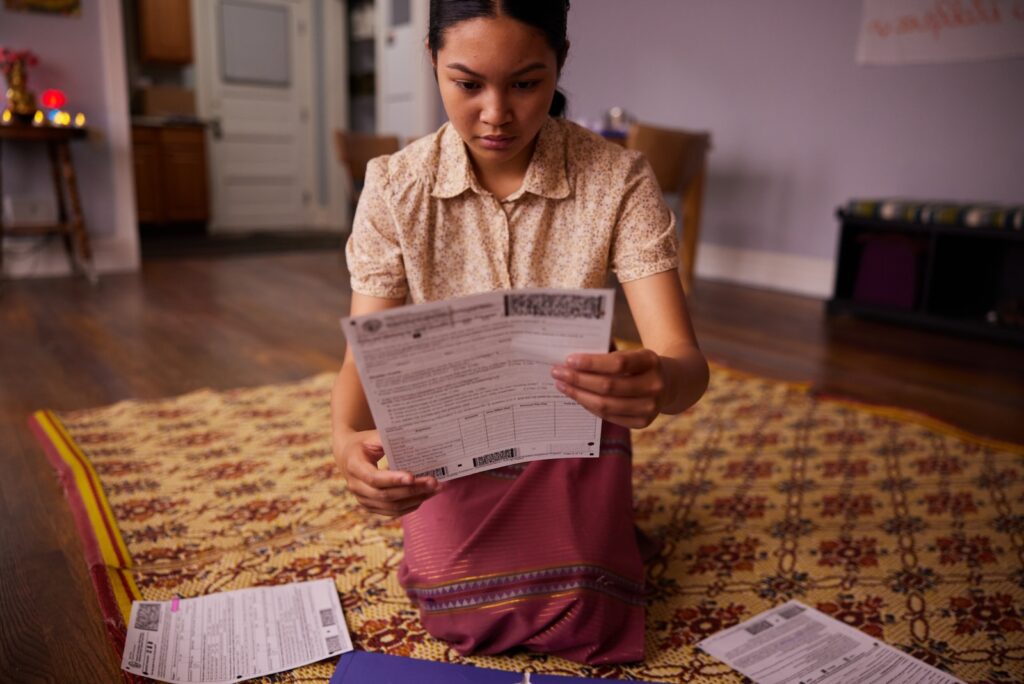

The stories they shared humbled me, a reminder that The American Dream is often out of reach, especially for those who come searching for it. In one apartment, I witnessed the struggles a South Asian family undertook to arrive in America, yet it was clearly only the beginning of their hardships. As I helped the children put away groceries donated by other tenants, it wasn’t enough to distract from hearing their mother’s frustrations in trying to navigate Chicago. Additionally, I watched a Hispanic mother and her three daughters’ lives become consumed in a vicious cycle of fundraising for their father to cross the border. While witnessing the family’s tribulations, I wondered about the costly nature of coming to the “Land of The Free,” weighing its worth in a new light.

These two interactions encapsulate the continual theme and message present throughout Port of Entry–how community, history, and human connection are integral to the immigrant experience. There is no overarching narrative or plot featured, merely a presentation of vignettes that are reflections of real experiences not regularly focused on in mainstream media. Port of Entry simply yet directly presents audiences with events they may never encounter in their own lives, succeeding in a noble, righteous, and important goal of making unique human experiences accessible to more people.

Above all, the most captivating, compelling element of Port of Entry is its performers. Since its founding, APTP’s Performing Ensemble has consisted of teens of color from first-generation or immigrant families. These performers play roles ranging from recently immigrated preteens who don’t speak English to elderly grandparents still struggling with assimilation. Other than their costumes, as I noticed no age makeup, the performers embodied characters only through body and voice.

It’s been a decade since I’ve seen such stellar performance work in Chicago. The last time was when seeing Michael Shannon onstage in a black box space. And, with all due respect, Mr. Shannon could learn a thing from the APTP Performing Ensemble. These teens truly embodied their characters, effortlessly conveying complex, heady emotions subtly through movement and tone.

In particular, I was floored by teens playing older or parental roles that were incredibly adult oriented. One featured a mother balancing the needs of the child she left behind in Latin America with the child she’s raising separately in America. I saw no teen performer, only an exhausted mother. Port of Entry is not only a credit to the entire Performing Ensemble’s talent, but also their maturity, compassion, and understanding as humans. The world needs more people capable of such skills, on and off the stage.